It’s occurred to me that I have been writing quite a bit about broadening participation in science lately and have not actually talked much about what science I have been up to. So here is a brief update about recent developments on that front.

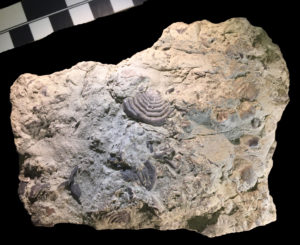

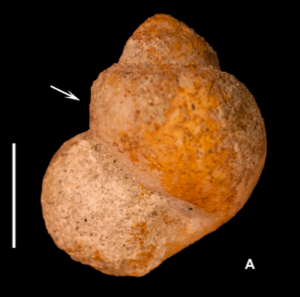

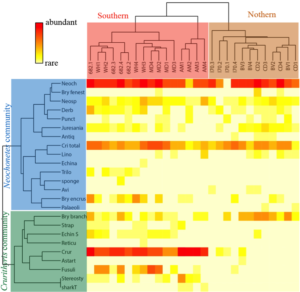

At the IGCP 653 meeting in Yichang, China, I presented new research on some very interesting and rare fossils from the lower part of the Cincinnatian Series. Over the past few years, I have been very fortunate to receive a series of rare fossils collected by some of the fantastic amateur paleontologists of the Dry Dredgers in Cincinnati, Ohio. In particular, Ron Fine, has collected some intriguing brachiopods from the lower Cincinnatian Kope Formation (Edenian Regional Stage) that look like they belong to lineages otherwise only known as invasive taxa from the upper Cincinnatian (Richmondian Regional Stage). These pre-Richmondian “invaders” comprise an interesting set of species that shed light on invasion dynamics in the fossil record.

At Yichang, I argued that interbasinal species invasions (or immigrations) could be considered in a hierarchical context, with ranks including ephemeral invasion, incursion epibole, and biotic immigration events. I am currently expanding this invasion hierarchy into a full article for Annual Reviews in Ecology and Evolutionary Systematics. (AREES), so I won’t elaborate here, but I think this is a really exciting and potentially transformative concept about the assembly of diversity through time.

At the GSA meeting in Seattle, I am presenting research related speciation mechanisms and how we can move from a basic correlation of diversity with Earth systems events to a causal mechanism for increasing diversity based on the process of speciation. Much of the arguments for this talk are in press already within my Lethaia paper (here).

So…for the near term, these are the scientific questions that I am investigating and the questions that keep me up at night: how do we really resolve speciation processes in the fossil record, how can we use that information to understand diversification during the Ordovician Radiation/Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event, and how do invasions (of varying intensities) contribute to diversity patterns of life through time?*

*obviously these questions are best addressed with data about articulated brachiopods from the Ordovician Period