It is difficult to describe this year’s GSA meeting in Denver. Overall, it was a great meeting, full of the usual pride in my students’ accomplishments, joy of reuniting with colleagues including many Stigall Lab alumni, nervousness about my own talks, and thrill of learning about the newest developments in the science of paleontology. But I will always remember this meeting for the Paleontological Society banquet.

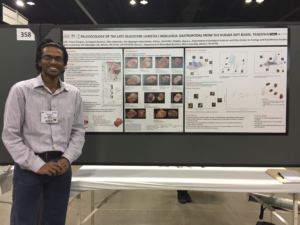

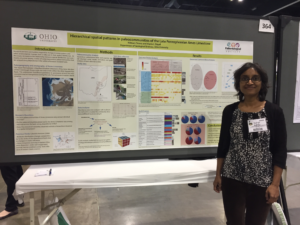

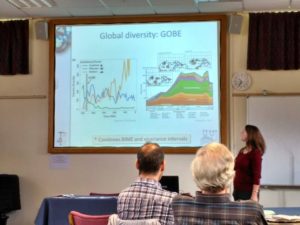

The Stigall lab was busy presenting cutting-edge science on a wide variety of topics. Current MS students Ranjeev Epa and Nilmani Perera gave excellent poster presentations about Oligocene freshwater gastropods from Tanzania and Pennsylvanian marine community ecology of Ohio, respectively. Recent alumnus Sarah Trubovitz gave a talk about her MS work on Ordovician brachiopod paleoecology, and I spoke about the importance of alternating dispersal and vicariance regimes in biodiversity accumulation.

We had a great Stig*Allstars (=name my alumni gave themselves) dinner to kick off the meeting. Getting together with this talented group of former students turned colleagues is always a highlight. They are doing such amazing work as PhD students and early career scientists. I’m so very proud of them and excited to see where their careers will go.

This year’s GSA, however, was really special as I was awarded the Charles Schuchert Award for Excellence and Promise in Paleontology from the Paleontological Society. This was the 45th time the Schuchert Award has been presented. It was only the 5th time that a woman received the award, and the first time a woman with children was the recipient. After receiving the award from the Paleontological Society president, Steven Holland, I was honored to be able to give a short acceptance speech to the nearly 400 paleontologists gathered at our annual banquet. I focused my remarks on the challenges to women and minorities in paleontology alongside the standard series of thank you’s. This the first time that increasing participation has been addressed specifically in an award speech, and I felt both very compelled and nervous about making these comments. I am very glad that I did! Continuing to engage in conversations about women and minority challenges are very important for continued progress in our (or any) discipline.

The full text of my speech is below, and it will eventually be published in the Journal of Paleontology.

RESPONSE BY ALYCIA L. STIGALL

For the Charles Schuchert Award, 25 September 2016Thank you, Bruce, for your generous words. I deeply thank the Paleontological Society for recognizing me with this honor. I truly am very grateful and humbled to be selected as the 2016 Schuchert Award recipient. As a brachiopod worker from Cincinnati, the Charles Schuchert award holds special significance to me. I am also deeply honored to now be included among the prestigious set of 44 prior awardees. It is particularly gratifying as I am only the fifth woman to receive this award, and first woman who was a mother at the time of the award.

I am extremely thankful to be a paleontologist today. Paleontology is becoming an ever more inclusive and collaborative science. As I look out from this podium, I see a wonderful diversity of paleontologists –diversity of scientific approaches, diversity of focal taxa, diversity of gender, diversity of ethnicities and nationalities. Our diversity makes our discipline stronger.

However, barriers to full and equitable participation in science for women and minorities remain considerable. Implicit bias, higher expectations, under recognition, harassment, and isolation remain substantial concerns. As a society and as individuals, we are taking positive steps to increase dialog, foster support groups, promote awareness, and tackle our own inherent biases. Like all women who continue in science, I have overcome such challenges in my career, but tonight I stand here excited and optimistic that the future of our discipline will be one of ever increasing inclusion.

I would not be here tonight without the support of my family, colleagues, and friends, and I’d like to take the rest of my time to recognize some of them. First I must thank my parents. As teachers, they have been steadfast in their support of my love for learning, rocks, and fossils. When I was a child, they took me to national parks in 47 states, they accompanied me to rock and mineral shows, gave me a copy of a 1962 Golden Guide to Fossils, and allowed me to disappear into the nearby stream to hunt fossils for hours at a time. Those early experiences surrounded by loving support gave me the confidence to truly pursue my goals and dreams.

As an undergraduate at the Ohio State University, I had the amazing good fortune to learn morphology and systematics (with a Swedish accent) from Stig Bergström who taught me the importance of deeply understanding a clade and of adopting promising new approaches during one’s career. Loren Babcock instilled in me a sense of boundless enthusiasm for prehistoric creatures. And Bill Ausich taught me how to be an excellent scientific citizen, the importance of loving your clade, and above all pursing excellence in science. I am so thankful for the enduring support of Bill and Stig, which has been instrumental in my development as a scientist.

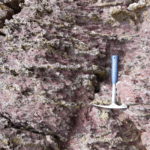

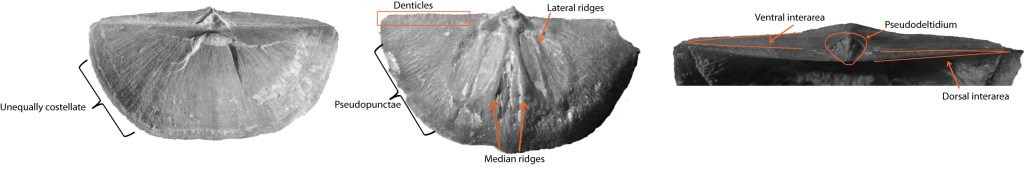

I graduated from OSU with a career goal to resolve early arthropod phylogeny–but quickly reoriented my research interests to studying the complex impacts of biogeography and ecological change on macroevolutionary patterns. In graduate school at the University of Kansas, I worked on phyllocarid crustacean phylogenetics of my master’s thesis, but rapid realized the limitations of working on uncommon fossils for my research agenda. So I shifted my focal taxon to rhynchonelliform brachiopods, and I haven’t look back. (Although I greatly enjoy working with conchostracans from time to time) Brachiopods are truly awesome.

Throughout graduate school, Bruce Lieberman was amazing mentor in every dimension of the word. He taught me how to construct a project, how to succeed in publications, and the importance of perseverance. Even beyond graduate school, Bruce’s promotion of my career has been immeasurable, and I thank him very deeply.

In my twelve years at Ohio University, I have been privileged to work with very supportive colleagues in our Geological Sciences department, an immensely talented set of paleontologists sprinkled across campus, and fantastic collaborators in the Patton College of Education. Working in a department with the master’s as our terminal degree offering, I’ve had the distinct pleasure of working very closely with each of my graduate students. My greatest scientific joy has been mentoring and encouraging my students—now numbering 13—as they develop from scientific novices to confident, accomplished scientists conducting research publishable in top journals. I am very proud of them, and certainly wouldn’t be standing here before you tonight without this exceptional group of students turned collaborators, many of whom are here to support me tonight.

Although I did not know many women paleontologist as a student, I have benefitted greatly from knowing and learning from many amazing women as a professional. In particular Margaret Fraiser, Sandy Carlson, Brenda Hunda, Lisa Park Boush, Dena Smith, and Peg Yaccobucci have been co-conspirators and role models in various ways. I thank the women who trailblazed in the cohorts ahead of mine, and I am greatly inspired by the women in the junior cohorts behind me.

I also thank my colleagues outside of this room. My approach to science has been considerably broadened and enriched by collaborations with modern biogeographers and ecologists as well my international colleagues with whom I’ve studied fossils on all seven continents.

Finally, and most importantly, I must thank my husband, Dan Hembree, who has been my partner in this journey since our first day of graduate school at Kansas. He has always believed in me, even when I did not. His friendship, laughter, encouragement, and discussions have made my science and my life so much richer, and I can’t imagine either without out him. Lastly, our children Max and Josie make everything awesome. It has been invigorating to re-explore the wonders of fossils through their young eyes.

Thank you again, to the members and Council of Paleontological Society for this recognition. I will strive to fulfill the promise inherent in this award and serve our community well in the years to come.

For my final adventure of the summer, I traveled to Ft. Lauderdale, Florida to present an invited talk about lessons learned from invasive species in the fossil record at the Ecological Society of America (ESA) meeting. I was very honored to be part of an exciting symposium titled: “

For my final adventure of the summer, I traveled to Ft. Lauderdale, Florida to present an invited talk about lessons learned from invasive species in the fossil record at the Ecological Society of America (ESA) meeting. I was very honored to be part of an exciting symposium titled: “