Thanks to a successful grant proposal to the College of Arts and Sciences Professional Development Fund (note: it’s always good to write proposals internal funding opportunities!), I was able to join the post-conference field trip to examine the Paleozoic evolution of the Welsh basin. The outcrops in Wales are famous for both their interesting geology and historical significance. The Cambrian, Ordovician, and Silurian systems were each named for Wales: Cambria was the Roman name for Wales, and the Ordovices and Silures were Welsh tribes.

During the trip, our fantastic field trip leader, Mark Williams (University of Leicester), developed the story of the Welsh basin from inception as part of the microcontinent Avalonia to the collision of Avalonia and Baltica at the end of the Ordovician and then the final collision with Laurentia during the Acadian Orogeny (learn about Welsh Geology here).

Our itinerary took us to southern Wales to sites around St. Davids, Marloes Peninsula, and Freshwater West as well as to a few locations in central Wales near New Quay. We examined mostly Cambrian through Devonian strata, with some bonus late Pre-Cambrian volcanics. We visited sites mapped by Murchinson, localities that contributed to the development of the classic Benthic brachiopod assemblages, well-studied exposures of the Old Red Sandstone, and newly recorded debris flows related to Ordovician glacial lowstands. Along the way, we were presented with a broad array of depositional environments, tectonic influences, and fossils (mostly trace fossils).

Overall it was a tremendous learning experience. I was impressed by the diversity of geology that could be observed in a small area—it’s definitely not the simple flat-lying rocks of the North American midcontinent! Visiting classic locations located in dramatic (or romantic as our leader liked to say) coastal scenery was thrilling. The discussions with my international colleagues (representing eight countries) in the field, in the car, and at meals were stimulating and very productive. I was able to meet and get to know quite a few new (to me) geologists with similar interests. Observing the same rocks and comparing interpretations is a rapid way to develop new friendships and potential collaborations. I am extremely glad that I was able to participate in this trip. There were not very many brachiopods, but the rest of the experience made that minor hardship very insignificant.

A brief travelogue with photos and comments:

Day 1: We drove from Ghent, Belgium to Piselli Hills, Wales. This was a LONG travel day (7:00am to 6:30pm in a minibus). But we took the ferry across the English Channel saw the fantastic White Cliffs of Dover (and also the correlative White Nose near Calais). Yay Cretaceous chalk! The geology was pretty boring after that (just very minor rolling hills with no outcrops) until we reached Wales. Wales is extremely complex geologically, so topography and outcrops became much more intriguing. We also experienced the expected misty rain of Wales upon arrival.

Day 2: We spent the morning on Pwell Deri Bay near Dinas Mawr examining Ordovician bimodal volcanics and graptolitic shales (although no one has seen a graptolite here in decades!) with some very cool pillow basalts at the base of the sequence. We were kept company by fantastic scenery, many shore birds, and a curious seal. Over lunch break, we explored St. Davids Cathedral, the location of the longest continuous Christian worship in Britian. The Norman cathedral was strategically located in a valley so the Vikings wouldn’t notice it and destroy it as they did the two prior cathedrals. Interesting intersection of geology and anthropology. We spent the afternoon at Porth Maen Melyn examining the shallow marine succession of Cambrian strata. On our way back to the hotel, we visited a Neolithic Burial Chamber dating to around the same time (and made of the same rocks) as Stonehenge. In fact, the rocks of Stonehenge were quarried from the Ordovician intrusive suite near our hotel, and then transported a long way over water to the Salisbury plains.

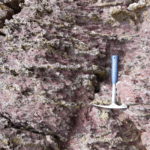

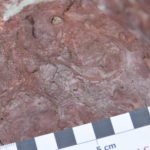

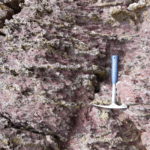

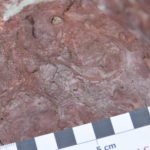

Day 3: Today focused on the Silurian of the Marloes Peninsula. The section is again shallow water through continental deposits that indicate the docking of Avalonia with Laurentia and associated basin inversion. This is a fun area for historical reasons, as Murchinson also mapped this coast. Although one formation was named “Coraliferous”, I was underwhelmed by the fossils. Sadly, these poor rocks have been faulted and subjected to low grade metamorphism, so while there are nice layers of brachiopods, they are very difficult to access. I felt very lucky to normally work on rocks like we have in Ohio. The continental deposits, “Old Red Sandstone”–now the Red Cliff Formation, however, were spectacular!

Day 4: We continued exploring the continental deposits of the Welsh basin margin at Freshwater West. As all of our exposures are coastal and the tidal range is immense!, we couldn’t begin geology until after lunch. So we made a historical excursion to Pembroke Castle in the morning. The castle was impressive and geologically situated (aren’t they all) on a limestone cliff, atop a cave, in fact. Our tour guide enthusiastically shared stories of the castle’s history and substantial importance (although perhaps overstated) in Engligh and world! history. Fun fact: because the 800 years old castle is made of limestone, little stalactites grow from the ceiling. After lunch, we headed back to the beach to explore more of the Old Red Sandstone and the Silurian to Devonian contact. Again, the paleosols and continental trace fossils (both root structures and burrows) were spectacular! The beach was also incredibly pleasant to walk along. It was interesting for me to compare the intertidal communities of Britian vs. those I know better from the Bahamas.

Day 5: We left the basin edge and went deep into the basin center (near New Quay) to investigate Ordovician to Silurian deep water deposits. We were impressed by the thickness of basinal deposits (several kilometers) vs. the relative thin marginal succession of the past few days (a few 100 meters). The basinal deposits included turbidites and debris flows in varying amounts. In some places, dramatic channel cuts were obvious, but at other sites quiet water trace fossils (like Nereites) were dominant. Certainly an interesting environment!

Day 6: We began our LONG drive back to Ghent. Most of the field party departed from Heathrow, but I traveled back to Belgium with the field trip leaders and van drivers. We left our hotel and 8am, and we arrived in Ghent at 10:30. It was a long day. But the Ghent Festival was happening, so Thijs Vandenbrouke (who organized the conference and field trip), Mark Williams, and I headed back to the medieval town center for one last dinner and beers. A great end to great trip.

Link to full Belgium/Wales Album

For my final adventure of the summer, I traveled to Ft. Lauderdale, Florida to present an invited talk about lessons learned from invasive species in the fossil record at the Ecological Society of America (ESA) meeting. I was very honored to be part of an exciting symposium titled: “

For my final adventure of the summer, I traveled to Ft. Lauderdale, Florida to present an invited talk about lessons learned from invasive species in the fossil record at the Ecological Society of America (ESA) meeting. I was very honored to be part of an exciting symposium titled: “